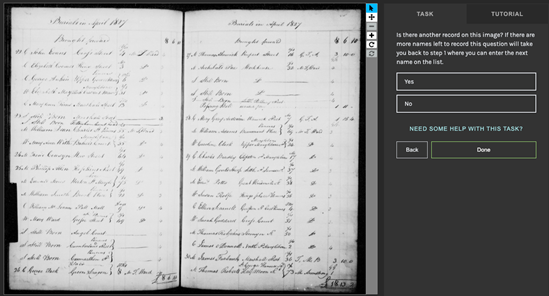

Archaeologists from MOLA Headland Infrastructure, working on High Speed 2, are inviting people to take part in a huge citizen science project - digitising 57,639 burial records that hold key details about the lives of Londoners in the 18th- and 19th-century. Would-be researchers can take part via the Stories of St James's Burial Ground website.

The records relate to St James’s Burial Ground, Euston, where over 31,000 burials were carefully excavated on behalf of CSjv, as part of HS2’s archaeology work between 2018 and 2019. The largest of its kind ever undertaken in the UK, the excavation provided an unprecedented opportunity to understand what it was like to live through a pivotal time in London’s history, when the Industrial Revolution was in full swing.

With excavations complete, archaeologists now want to combine their findings with details contained in the burial ground records, to delve even deeper into the site’s history. The project will create a searchable, digital archive to develop a better understanding of the people buried at St James’s, revealing crucial details about their lives and opening the doors to further research.

Helen Wass, Head of Heritage at HS2 Ltd, said:

“At HS2, we are not only building for the future, but are preserving our past. As we excavated St James’s burial ground, all remains were treated with due diligence, care and respect, and this is a great example of how we are honouring the lives of those buried there by discovering their stories.”

Participants will use the project website to decipher handwritten burial records, logging key details like names, addresses and causes of death. They will join a global team of researchers working together to unlock the stories of the burial ground, collaborating with world-class archaeologists and bringing their own unique and valuable perspectives to the project.

No previous experience is required – just a willingness to learn new computer skills and do some problem solving –and there is no minimum time commitment.

Robert Hartle, a Senior Archaeologist at MOLA Headland Infrastructure who worked on the excavation, said:

“The people buried in St James’s burial ground include individuals from all walks of life; men, women and children, paupers and nobility, artists and soldiers, inventors and industrialists. But the archaeology is only the beginning. The large number of individuals at St James's who are identifiable via surviving name plates gives us an unprecedented chance to unlock avenues for further research, to match the physical remains of people and their burials with the historical records of the lives they led.”

“The Stories of St James’s Burial Ground digitisation project is a unique opportunity to make a genuine contribution to our ongoing archaeological research and make connections that will shed new light on ordinary people, all too often forgotten to history.”

Paul McGarrity, a Community Engagement Project Officer from MOLA Headland, said:

“Volunteers have played a vital part of this project from the very start, recording biographical details inscribed on 18th- and 19th-century gravestones at St James’s back in Summer 2018. It is wonderful to now be able to invite people around the world to join the research team, and I am excited to see what we can learn from them.”

Volunteers who took part in the 2018 gravestone recording project said:

“As someone interested in London history, it was particularly enjoyable being involved (even in a small way) in uncovering actual history in a hands-on way. There was no telling what you would find...”

“It was interesting to learn in more detail about the area and to take an imaginary glimpse into the people’s lives. To be involved in an archaeology site was a privilege.”

ENDS

The Stories of St James’s Burial Ground so far...

Burial records have proved to be invaluable to the team of archaeologist researching the site, allowing key biographical details to be pieced together about those buried at St James’s. Here are just a few of the people whose stories have been brought to light so far:

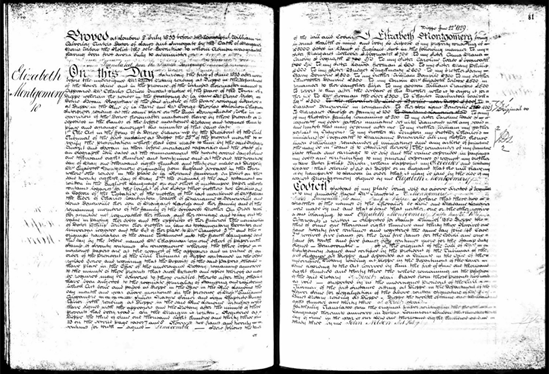

Elizabeth Montgomery

During the excavation, a unique coffin was found. Made from wood wrapped with lead, it was an unusual shape and size, and had decorations unlike any the team had seen before. By looking at burial records, newspaper articles and wills, archaeologists were able not only to explain the coffin’s unusual shape, but also to identify its owner and piece together a detailed picture of her final days.

Elizabeth Montgomery died on 28 May 1833 in Dieppe, France, aged 40. Her unusual coffin was probably made by a French coffin maker, rather than made in London by one of the local craftsmen who served most patrons at St James’s. Elizabeth wrote in her will of her wish to be returned to London to be buried alongside her ‘dearest’ late husband Reverend George Montgomery should she die abroad, and thanks to a note in The Times newspaper on June 11, 1833, we know that she got her wish. Her coffin was brought to an address in Cavendish Square, Marylebone, and from there to St James’s for burial. Her will also mentions a collection of miniature portraits. It seems that one of these precious miniatures was placed into her coffin, where it was found by the archaeological team nearly 200 years later.

Matthias Tomick

Sometimes archaeological evidence highlights discrepancies in the burial records, demonstrating the value of pairing historical sources and archaeological data. Matthias Tomick of ’Broad Street, Carnaby Market’ was buried in 1794, following his death aged 66 ‘of a decline’. An additional note on his burial entry records his height as 7ft 10 inches. However, when archaeologists excavated Tomick’s burial, they found that he was between 6ft 6 and 6ft 8 inches tall. This discrepancy may have been the result of a miscommunication, rather than an exaggeration, with the length of an extra-long grave being misconstrued as the height of the deceased.

Frederick James and Jane Elizabeth Havell

Burial records enabled the team to identify the final resting places of Frederick and Jane Havell. Frederick James Havell came from a family of artists. Originally a steel engraver in line and mezzotint, Havell, together with his brother William and fellow engraver James Tibbits Willmore, experimented with early photography techniques, presenting their Cliché Verre process at the Royal Society in London in 1839. Sadly, later that year he was admitted to and then died at Bethlem Hospital with ‘the occurrence of insanity’. His condition may well have been caused by erethism, also known as ‘mad hatter syndrome’, because of prolonged exposure to mercury vapours from photographic experiments. Jane Elizabeth Havell, his wife, died six years later and was buried in the same grave with a picture frame placed face-down on her chest. No picture survived within the glass and wood frame, but this personal object is a poignant reminder of her family connections.